Alarming Inflammation: A Guide to Meningitis

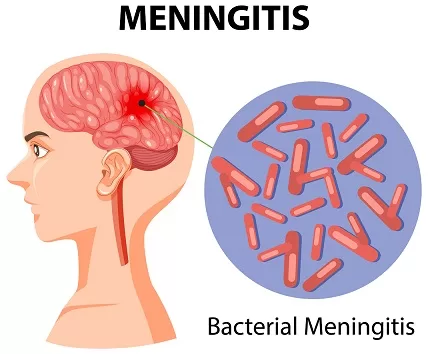

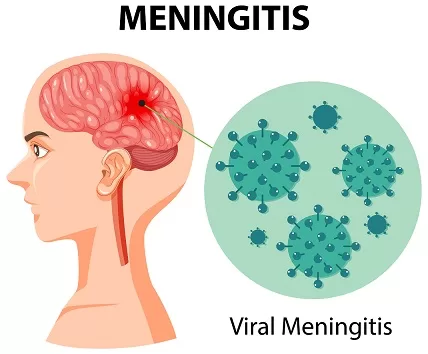

Meningitis, an inflammation of the meninges (the protective membranes surrounding the brain and spinal cord), can be a frightening illness. While it can be serious, early diagnosis and treatment are crucial for preventing potentially life-threatening complications. This blog delves into the different types of meningitis, the warning signs and symptoms, diagnosis methods, treatment approaches, prevention strategies, and prognosis.

A Spectrum of Invaders: Types

Meningitis can be classified into several types based on the causative agents. Understanding these types is essential for accurate diagnosis and effective treatment.

1. Bacterial Meningitis

Bacterial meningitis is a severe and potentially life-threatening condition that requires immediate medical attention.

- Common Causes:

- Streptococcus pneumoniae meningitis (pneumococcal meningitis): The most common cause in adults and children.

- Neisseria meningitidis (meningococcal meningitis): Known for outbreaks in close communities; can cause rapid progression.

- Haemophilus influenzae type b (Hib): Less common due to vaccination.

- Listeria monocytogenes: Affects newborns, elderly, and immunocompromised individuals.

- Group B Streptococcus: A common cause in newborns.

2. Viral Meningitis

Viral is more common and generally less severe than bacterial. It often resolves without specific treatment.

- Common Causes:

- Enteroviruses: The most common cause, especially in children.

- Herpes Simplex Virus (HSV): Can cause severe cases, particularly HSV-2.

- Varicella-zoster Virus: Causes chickenpox and shingles.

- Mumps Virus: Rare in vaccinated populations.

- HIV: Can cause chronic meningitis.

3. Fungal Meningitis

Fungal meningitis is rare and typically occurs in individuals with weakened immune systems.

- Common Causes:

- Cryptococcus neoformans: Common in immunocompromised individuals, such as those with HIV/AIDS.

- Histoplasma: Found in certain geographic areas, particularly in the Midwest USA.

- Coccidioides: Endemic to the southwestern USA and parts of Central and South America.

4. Parasitic Meningitis

Parasitic meningitis is rare and can be caused by various parasites.

- Common Causes:

- Naegleria fowleri: A free-living amoeba found in warm freshwater; causes primary amebic meningoencephalitis (PAM), which is usually fatal.

- Angiostrongylus cantonensis: A rat lungworm that causes eosinophilic meningitis; found in certain tropical and subtropical regions.

- Baylisascaris procyonis: A roundworm found in raccoons; causes severe neurologic disease.

5. Non-Infectious Meningitis

It can result from a variety of non-infectious causes and is not contagious.

- Common Causes:

- Autoimmune Diseases: Conditions like lupus or sarcoidosis.

- Medications: Certain drugs can cause drug-induced meningitis (e.g., nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, antibiotics).

- Cancer: Cancer can cause carcinomatous meningitis, where cancer cells spread to the meninges.

- Brain Surgery: Post-surgical inflammation can lead to non-infectious meningitis.

Pathogenesis

Meningitis is an inflammation of the protective membranes covering the brain and spinal cord, known collectively as the meninges. The pathogenesis involves a series of steps from the initial exposure to the causative agent to the inflammatory response in the central nervous system (CNS).

Bacterial Meningitis

- Colonization and Invasion:

- Entry: The bacteria usually enter the body through the respiratory tract. Common pathogens include Streptococcus pneumoniae, Neisseria meningitidis, and Haemophilus influenzae.

- Colonization: These bacteria colonize the nasopharyngeal mucosa. They evade the host’s immune system using various mechanisms, such as producing IgA protease which degrades immunoglobulin A (IgA), a key component of mucosal immunity.

- Evasion of Host Defenses:

- Penetration of Mucosal Barrier: Bacteria penetrate the mucosal barrier and enter the bloodstream. This can occur through mechanisms like disrupting tight junctions between epithelial cells or by being taken up by host cells in a process resembling phagocytosis.

- Survival in the Bloodstream: Once in the bloodstream, bacteria must evade the immune system. They use strategies like capsular polysaccharides to resist phagocytosis and complement-mediated lysis.

- Crossing the Blood-Brain Barrier (BBB):

- Adhesion to Endothelial Cells: Bacteria adhere to the endothelial cells of the BBB using specific adhesins.

- Translocation Across the BBB: The pathogens cross the BBB through mechanisms such as transcellular traversal, paracellular traversal, or by infecting and being transported by immune cells (Trojan horse mechanism).

- CNS Invasion:

- Once inside the CNS, bacteria multiply in the cerebrospinal fluid (CSF), an environment with limited immune defenses.

- Release of Inflammatory Mediators: Bacterial components like lipopolysaccharides (LPS) in Gram-negative bacteria or teichoic acids in Gram-positive bacteria trigger a robust inflammatory response.

- Cytokine Production: This response includes the release of pro-inflammatory cytokines (e.g., IL-1, IL-6, TNF-α) by resident macrophages (microglia) and other immune cells. These cytokines increase the permeability of the BBB, allowing more immune cells and proteins to enter the CSF.

- Inflammation and Tissue Damage:

- Recruitment of Immune Cells: Neutrophils and other immune cells infiltrate the CSF, releasing enzymes and reactive oxygen species that cause tissue damage.

- Cerebral Edema: The inflammatory process leads to increased permeability of the BBB, resulting in vasogenic edema, cytotoxic edema, and interstitial edema.

- Increased Intracranial Pressure (ICP): The combination of edema and increased CSF production leads to elevated ICP, which can cause further neuronal damage and compromise cerebral blood flow.

Viral Meningitis

- Entry and Replication:

- Viruses typically enter the body via the respiratory or gastrointestinal tracts and initially replicate at the entry site.

- Common viral pathogens include enteroviruses, herpes simplex virus (HSV), and mumps virus.

- Dissemination to CNS:

- The virus disseminates to the CNS through the bloodstream (hematogenous spread) or via peripheral nerves (retrograde axonal transport).

- Invasion and Immune Response:

- Viruses cross the BBB through mechanisms like infecting endothelial cells or utilizing infected immune cells to gain access to the CNS.

- The immune response involves the activation of microglia and astrocytes, production of cytokines, and recruitment of T cells to control the infection.

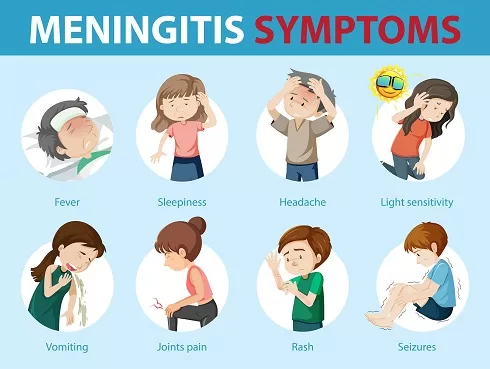

Warning Signs You Shouldn’t Ignore

General Symptoms

1. Fever:

- A high fever is one of the most common symptoms, often accompanied by chills.

2. Headache:

- Severe and persistent headaches are typical, sometimes described as the worst headache ever experienced.

3. Stiff Neck:

- Neck stiffness and pain, making it difficult to touch the chin to the chest, is a classic sign of meningitis.

4. Photophobia:

- Sensitivity to light can cause discomfort and exacerbate headaches.

5. Nausea and Vomiting:

- These symptoms often accompany the headache and fever.

6. Altered Mental Status:

- Confusion, irritability, lethargy, and difficulty waking up are serious symptoms indicating brain involvement.

7. Seizures:

- Seizures may occur in severe cases.

Symptoms in Different Age Groups

Adults and Older Children:

- Sudden high fever

- Severe headache that seems different from normal

- Stiff neck

- Sensitivity to light (photophobia)

- Nausea and vomiting

- Confusion and difficulty concentrating

- Sleepiness or difficulty waking up

- Seizures

- Loss of appetite and thirst

- Skin rash (in some cases, especially with meningococcal meningitis)

Infants and Young Children:

- High fever

- Constant crying, often high-pitched

- Excessive sleepiness or irritability

- Poor feeding or refusing to feed

- Vomiting

- Bulging fontanelle (soft spot on a baby’s head)

- Stiffness in the body and neck

- Seizures

- Difficulty waking from sleep

Newborns:

- Poor feeding

- Vomiting

- High-pitched cry

- Irritability or lethargy

- Fever or lower-than-normal temperature

- Jaundice (yellowish skin and eyes)

- Bulging fontanelle

- Rigidity or limpness

Additional Symptoms Based on Types

Bacterial Meningitis:

- Rapid onset of symptoms

- Severe and potentially life-threatening if not treated promptly

- Skin rash that does not blanch (turn white) when pressed, indicating meningococcal meningitis

Viral Meningitis:

- Symptoms may be similar to bacterial meningitis but are usually milder

- Often follows a respiratory illness or gastrointestinal infection

- Complete recovery is common without specific treatment

Fungal Meningitis:

- Gradual onset of symptoms

- More common in individuals with weakened immune systems

- Symptoms may be similar to bacterial meningitis but progress more slowly

Parasitic Meningitis:

- Symptoms can vary based on the parasite

- Naegleria fowleri infection (primary amebic meningoencephalitis) causes rapid onset of symptoms similar to bacterial meningitis but is usually fatal

Non-Infectious Meningitis:

- Symptoms can be similar to infectious meningitis

- Related to underlying conditions such as autoimmune diseases, cancer, or reactions to medications

Remember: If you experience any combination of these symptoms, especially a sudden high fever, severe headache, and stiff neck, seek immediate medical attention. Early diagnosis and treatment are crucial for preventing complications.

Unveiling the Culprit: Diagnosis

Diagnosing meningitis involves a combination of clinical evaluation, laboratory testing, and imaging studies. Prompt and accurate diagnosis is critical for effective treatment and to reduce the risk of complications. Here’s an overview of the diagnostic process:

1. Medical History and Physical Examination

Medical History:

- Symptom Onset and Duration: Information about the onset, severity, and duration of symptoms.

- Exposure History: Recent exposure to individuals with similar symptoms, travel history, and potential contact with infectious agents.

- Vaccination Status: Previous vaccinations against common pathogens like Haemophilus influenzae, Neisseria meningitidis, and Streptococcus pneumoniae.

Physical Examination:

- General Examination: Checking for fever, rash, and overall appearance.

- Neurological Examination: Assessing for signs of meningeal irritation such as nuchal rigidity (stiff neck), Brudzinski’s sign (involuntary lifting of the legs when the neck is flexed), and Kernig’s sign (pain on extending the knee when the hip is flexed).

- Skin Examination: Looking for petechial or purpuric rash, which may suggest meningococcal meningitis.

2. Laboratory Tests

Blood Tests:

- Complete Blood Count (CBC): To check for elevated white blood cells, indicating infection.

- Blood Cultures: To identify bacteria present in the blood.

- Inflammatory Markers: Elevated C-reactive protein (CRP) and erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR) may indicate inflammation.

Lumbar Puncture (Spinal Tap):

- Cerebrospinal Fluid (CSF) Analysis: This is the cornerstone of diagnosis.

- CSF Cell Count: Elevated white blood cells indicate infection.

- CSF Glucose Level: Low glucose levels suggest bacterial infection.

- CSF Protein Level: Elevated protein levels indicate inflammation.

- Gram Stain and Culture: To identify the specific bacteria.

- Polymerase Chain Reaction (PCR): To detect viral DNA or RNA, particularly for viral meningitis.

- Antigen Tests: To detect specific pathogens (e.g., Cryptococcus antigen for fungal meningitis).

3. Imaging Studies

Computed Tomography (CT) Scan or Magnetic Resonance Imaging (MRI):

- Indications: Performed before lumbar puncture if there are signs of increased intracranial pressure, focal neurological deficits, or altered mental status.

- Findings: Helps to identify complications such as brain abscess, hydrocephalus, or subdural empyema.

4. Additional Diagnostic Tests

Chest X-ray:

- To identify primary sources of infection such as pneumonia, which can lead to secondary meningitis.

Urinalysis and Culture:

- To rule out urinary tract infection as a potential source of systemic infection.

Specific Tests for Immunocompromised Patients:

- HIV Testing: As immunocompromised patients are at higher risk for certain types of meningitis.

- Fungal and Mycobacterial Cultures: For patients with suspected fungal or tuberculosis meningitis

Battling the Infection: Management

The management of meningitis varies based on the type and cause of the infection. Early and appropriate treatment is critical to reduce the risk of complications and improve outcomes.

1. Bacterial Meningitis

Immediate Medical Attention:

- It is a medical emergency. Prompt hospitalization and treatment are essential.

Antibiotic Therapy:

- Empiric Antibiotics: Initiated as soon as bacterial meningitis is suspected, even before the causative organism is identified. Common choices include:

- Ceftriaxone or Cefotaxime: Broad-spectrum cephalosporins.

- Vancomycin: To cover for resistant Streptococcus pneumoniae.

- Ampicillin: Added in neonates, elderly, or immunocompromised patients to cover Listeria monocytogenes.

- Targeted Antibiotics: Adjusted based on culture results and antibiotic sensitivity.

Corticosteroids:

- Dexamethasone: Administered before or with the first dose of antibiotics to reduce inflammation and neurological complications, particularly in cases of pneumococcal meningitis.

Supportive Care:

- Hydration and Electrolyte Management: Ensuring proper fluid balance.

- Antipyretics: To control fever.

- Analgesics: To manage pain and discomfort.

Monitoring and Complications Management:

- Intracranial Pressure (ICP) Monitoring: For patients with signs of increased ICP.

- Seizure Management: Anticonvulsants if seizures occur.

- Intensive Care: For severe cases, monitoring in an ICU may be necessary.

2. Viral Meningitis

Supportive Care:

- Rest and Hydration: Ensuring adequate fluid intake.

- Pain Relief: Analgesics such as acetaminophen or ibuprofen for headache and fever.

- Antiemetics: To manage nausea and vomiting.

Antiviral Therapy:

- Specific Antivirals: For certain viral infections, such as:

- Acyclovir: For herpes simplex virus meningitis.

- Antiretroviral Therapy (ART): For HIV-associated meningitis.

Prognosis:

- Most cases of viral infection are self-limiting and resolve without specific treatment. Patients generally recover fully with supportive care.

3. Fungal Meningitis

Antifungal Therapy:

- Amphotericin B: Often the first-line treatment for severe fungal infections like Cryptococcus.

- Fluconazole: For less severe cases or as a step-down therapy after initial treatment with amphotericin B.

- Itraconazole: For histoplasmosis or coccidioidomycosis.

Supportive Care:

- Similar supportive measures as for bacterial and viral meningitis.

Prognosis:

- Dependent on the patient’s overall health and immune status. Immunocompromised individuals, such as those with HIV/AIDS, may require long-term antifungal therapy and close monitoring.

4. Parasitic Meningitis

Antiparasitic Therapy:

- Miltefosine: For Naegleria fowleri infection, though the prognosis is often poor despite treatment.

- Albendazole or Thiabendazole: For other parasitic infections like angiostrongyliasis.

Supportive Care:

- Intensive supportive care is often required.

Prognosis:

- Varies significantly depending on the parasite and timeliness of treatment. Naegleria fowleri infection is typically fatal.

5. Non-Infectious Meningitis

Treatment of Underlying Condition:

- Autoimmune Diseases: Immunosuppressive therapies such as corticosteroids or other immunomodulatory drugs.

- Medication-Induced: Discontinuation of the offending drug.

- Cancer-Related: Treatment of the primary malignancy, which may involve chemotherapy, radiation, or surgery.

Supportive Care:

- Similar supportive measures as for infectious meningitis.

Prevention is Paramount

Preventing meningitis involves a combination of vaccination, healthy practices, and awareness of the risk factors associated with different types . Here’s an overview of the strategies for prevention:

1. Vaccination

Vaccination is the most effective way to prevent certain types of meningitis. Key vaccines include:

Bacterial Meningitis:

- Haemophilus influenzae type b (Hib) Vaccine: Protects against Hib, a commonest cause of bacterial infection in children.

- Pneumococcal Conjugate Vaccine (PCV13) and Pneumococcal Polysaccharide Vaccine (PPSV23): Protect against Streptococcus pneumoniae.

- PCV13: Recommended for all children under 2 years and certain older children and adults with specific health conditions.

- PPSV23: Recommended for adults 65 years and older, and for younger adults with specific health conditions.

- Meningococcal Vaccines: Protect against Neisseria meningitidis.

- MenACWY Vaccine: Covers serogroups A, C, W, and Y. Recommended for adolescents, with a booster dose in late adolescence.

- MenB Vaccine: Covers serogroup B. Recommended for individuals at increased risk, including those in outbreak settings and certain age groups.

Viral Meningitis:

- Measles, Mumps, and Rubella (MMR) Vaccine: Protects against mumps and measles.

- Varicella Vaccine: Protects against chickenpox.

- Influenza Vaccine: Annual flu vaccination can help prevent influenza-related viral meningitis.

2. Healthy Practices and Hygiene

Good hygiene and healthy practices can reduce the risk of contracting infections:

- Handwashing: Regular and thorough handwashing with soap and water, especially after being in crowded places or after coughing and sneezing.

- Respiratory Hygiene: Covering mouth and nose with a tissue or elbow when coughing or sneezing. Proper disposal of tissues and handwashing afterward.

- Avoiding Close Contact: Minimizing close contact with individuals who are sick, especially those with respiratory infections.

- Food Safety: Proper handling, cooking, and storing of food to avoid infections like Listeria.

3. Environmental and Lifestyle Measures

Environmental and lifestyle measures can also help in prevention:

- Avoiding Contaminated Water: Refraining from swimming in warm freshwater bodies known to harbor Naegleria fowleri.

- Safe Practices for Immunocompromised Individuals: HIV-positive individuals should adhere to their antiretroviral therapy and take prophylactic medications as recommended to prevent opportunistic infections.

4. Prophylactic Antibiotics

For close contacts of individuals with bacterial meningitis caused by Neisseria meningitidis or Haemophilus influenzae type b:

- Antibiotic Prophylaxis: Close contacts may be prescribed antibiotics such as rifampin, ciprofloxacin, or ceftriaxone to prevent infection.

5. Public Health Measures

Public health strategies to control the spread of meningitis:

- Outbreak Management: Quick identification and response to outbreaks, including vaccination campaigns and public health messaging.

- Surveillance Programs: Monitoring and reporting cases of meningitis to identify and respond to outbreaks promptly.

Meningitis Isolation Precautions:

General Precautions:

- Hand Hygiene: Rigorous handwashing with soap and water or using alcohol-based hand sanitizers.

- Personal Protective Equipment (PPE): Use of gloves, masks, and gowns when handling patients.

- Patient Placement: The patient should be placed in a private room or cohorted with another patient with the same infection in Neisseria meningitidis and private room in immunocompromise patients.

- Duration: Droplet precautions should continue for at least 24 hours after the initiation of effective antibiotic therapy.

- Visitor Restrictions: Limit visits to immediate family and essential personnel; ensure visitors wear masks.

Prognosis

The prognosis depends on the cause and promptness of treatment:

Bacterial

- Prognosis: Can be fatal if not treated promptly. Even with treatment, there may be long-term complications like hearing loss, cognitive impairments, or seizures.

Viral

- Prognosis: Generally better than bacterial infection. Most patients recover fully, though some may experience lingering headaches or fatigue.

Fungal and Parasitic

- Prognosis: Varies depending on the patient’s overall health and the speed of treatment. Immunocompromised individuals may have a poorer prognosis.

Non-Infectious

- Prognosis: Depends on the underlying cause. Often resolves with appropriate treatment of the primary condition.

Conclusion

Meningitis is a medical emergency that requires swift diagnosis and treatment. Understanding the different types, their symptoms, and appropriate management strategies can significantly improve patient outcomes. Preventive measures, particularly vaccination, are crucial in reducing the incidence of this serious condition. If you suspect meningitis, seek immediate medical attention to ensure the best possible prognosis.